“…privileged to live one day as free people, namely as people who refuse to exert, as well as to be subject to atrocity.”

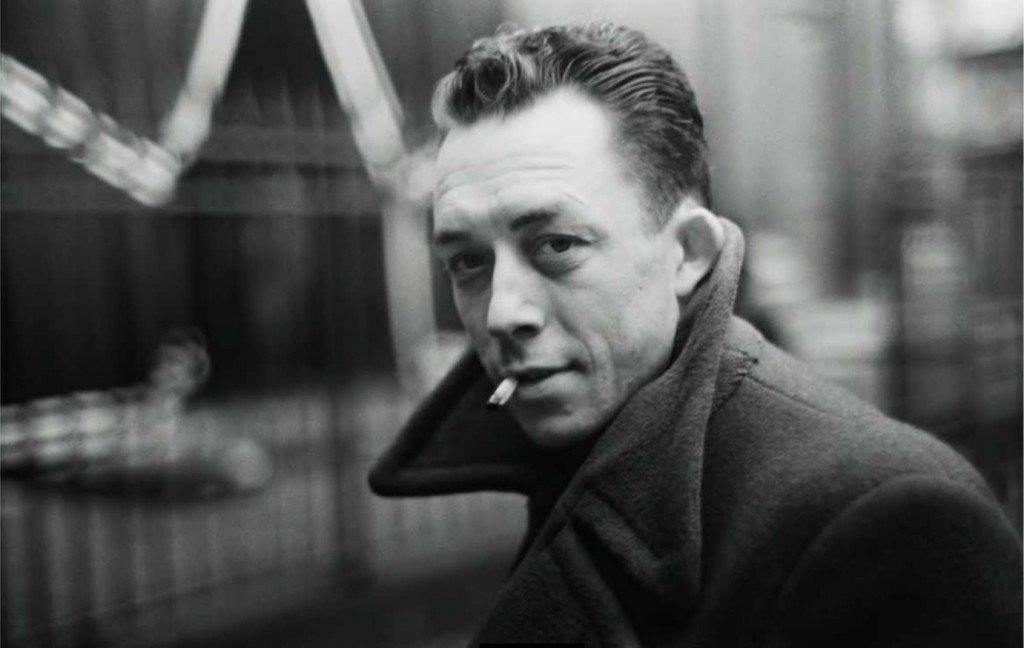

Albert Camus

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Imagine three men before the firing squad.

The first one is an angular old man who faces fearlessly the barrels of the guns that point at him, shouting: “I fear you not!”

The second one looks like a lemur. With bulging eyes he stares the guns with fear and anticipation.

The third one could be Humphrey Bogart. He knows that they point at him and the command will be given any second. But he has turned his head to the other side, smoking and watching the billows of smoke twisting and turning chaotically before they dissolve.

~

Those were the writers of my first youth.

Kazantzakis was the first, who haunted many adolescents’ minds by coining phrases like “go where you can’t reach” and “overstrain me, no matter if I break”. His books, and Nietzsche’s too, were like lion’s food to me. The man who stared the void in the eyes, without fear and hope.

A teacher introduced me to the second one. “Have you read Kafka?” she asked me. When I told her that I only knew him by name, she gave me his book “The trial” with a smile on her face. I figured out pretty soon the reason of this smile.

Books that seemed as if they were written between the sleep and alertness, almost nightmarish ones, yet you don’t want to wake up. I can’t remember anymore whether I dreamt or read some scenes from the incomplete “Amerika”.

He was courageous, too, before life and death but in his own unique way, like a psychopath clown who slashes you with a machete as he’s laughing – and on the background circus music can be heard.

And then it was Camus.

Succinct, but to the point. Reflective, but passionate. Masculine, but far from vulgar.

Standing on his own, too.

~

Many people think that Camus belonged to existentialism, the dominant literary/philosophical clique of postwar Europe. This is far from truth. Camus right from the start came face-to-face with the existentialists and also came into conflict with their high priest Jean-Paul Sartre and their high-priestess, Beauvoir.

He also came into conflict with the communists (a period of time when it was unthinkable to be an intellectual but not a Marxist), with the fascists, the Nazis, the clergymen, the surrealists, the colonialists French and with the fundamentalists Algerians.

“Every ideology”, he wrote in his book ‘The Rebel’, “discards all others as definitely misleading. That’s when we begin to kill.”

He writes also:

“Marx didn’t taught me freedom, misery did”.

~

Albert’s parents were forced to immigrate from Alsace to Algeria to escape the jaws of hunger, but they had no better luck there.

His father was killed in WWI six months after the birth of his son.

Catherine Camus moved to Algiers, to the slum of Belcourt which was inhabited by Arabians, Jews, Spanish, Maltese, Italians, Greeks and French. She cleaned houses and did anything else she could in order to survive, but she was sickly, both in body and mind.

Albert went to school whenever he felt like to, until he met the man that turned him into Camus we all know.

That man was a teacher, Louis Germain, who dedicated himself to this orphan with paternal love, giving him extra lessons for free, convincing his mother that the kid should take exams for the scholarship that would allow him to continue to high school.

Camus acknowledged his debt to his teacher when he was awarded with the Nobel Prize and dedicated him the Banquet Speech.

~

He earned a scholarship for the high school but there he had to face as destitute the sons of the rich middle-class people.

“I felt infinite strengths within me, all I had to do was find a way to use them. It was not poverty that got in my way: in Africa the sun and the sea cost nothing. The obstacle lay rather in prejudices or stupidity.”

Camus set his mind on prevailing. He became the school’s best student to win his teachers over and also exceptionally good at sports to win his classmates over.

Until he left he was nicknamed “the little prince”.

While he prepared for his philosophy studies at the University he got tuberculosis for the first time, a common disease at Belcourt’s slum. He was hospitalized for a year and when he was discharged he picked up his studies from where he left them off.

~

In 1933, when Hitler rose to power and Malraux’s “Man’s Fate” was published, the twenty-year-old Camus discovered writing and communism. He would honour the first till the end of his days, but he would remain a communist only for two years.

Camus joined the activities of the “Algerian People’s Party” but in 1935 the guidelines from Moscow demanded that the activities of the locals in Algiers should be watched closely in case they deviate from Stalin’s line and dogma.

Camus, like T.E. Lawrence, «refused to fall in line with these opportunistic orders and ended up to cut every bond with the communist party.”

“Where lie thrives”, he says, “is where tyranny is heralded and preserved”.

He completed his PhD in Philosophy and founded the independent troupe named “Theatre of the Team”. Camus always held the view that theatre was the highest form of art.

He works as a journalist, writes and stages theatrical plays, he starts with “The Outsider” (also “The Stranger”).

When Hitler invaded Poland and “took by surprise” many who held moderate views, he wrote:

“You have lived for so long in the hatred of this beast, it is before your eyes and yet you are unable to see it. So few things have changed. Later, beyond any doubt, mud, blood and utter disgust will follow. But today we come to the conclusion that the initiation of war is the same with the initiation of peace: people and heart are unaware of it.”

~

In 1941 he finished “The Myth of Sisyphus” and joined the French Resistance.

“I understood then that I hated violence less than the institutions of violence.”

After the liberation (and another attack of tuberculosis) Gallimard, Camus’ publisher, succumbed to Malraux’s pressure and printed “The outsider” under the impression that sales wouldn’t pass the 1,000 mark. They were wrong.

Along with “The Myth of Sisyphus” that was published a year later, the world saw existentialism’s rival. On the one hand an entire movement, on the other a heavy smoker who would never describe himself as a philosopher.

~

In 1948 the Eastern Europe becomes prey to Stalin’s dictatorship.

Camus’ reaction was a series of articles.

“When a worker, somewhere in the world, approaches a tank with his bare fists and cries out that he’s not a slave, what are we if we remain indifferent?”.

Yet while attacking Stalinism, he publicized a year later a plea for the lives of the convicted Greek communists.

In 1951 publishing of “The Rebel” fell like a bomb. Camus is censured by right and left wing (with Sartre on the head), by clergymen and atheists. His “philosophy” is one against dogmatism, of every nature, and in favour of man.

“The rebel himself wants to be all or nothing” he writes.

What could possibly a man do against this greedy system?

“It’s all wrong designed, my dear” he wrote at “The Plague”. “No matter how far I go back, I remember that it took only a man who overcame his fear and rebelled to make their machine creaking. I do not imply that it stops altogether, not by a long chalk. Yet it creaks and sometimes it really breaks down”.

He keeps on writing, producing plays and making political interventions when necessary.

Even his “enemies” testified his kindness and respect that were evident to the way he treated the others. “He neglected his glory” writes Beauvoir, “and preserved a hope for the man of the people that many regarded as naïve.”

In 1956 he published his last novel “The Fall” where he developed an older thought of his “There is but one truly serious philosophical problem and that is suicide”.

Three months later he was awarded the Nobel Prize in literature and two years later he died in a high-speed car accident with Gallimard’s car – around the age that Lawrence did.

~

“Naïve” till the end, he wrote:

“If I had to write a book on morality, it would have a hundred pages and ninety-nine would be blank. On the last page I should write: “I recognize only one duty, and that is to love.”

~

I drew information from P. Ginestier’s book: “La Pensee de Camus”

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~